- Home

- Cary Fagan

The Old World and Other Stories Page 4

The Old World and Other Stories Read online

Page 4

It’s cold. We’ve been walking for almost two hours. I thought we were going to find the road and end up in a restaurant. All I can think of is soup.

The world looks different when you’re gazing up. Your own life looks different.

Life looks different when you’re eating a bowl of soup.

Just come down here. Do it for me.

Fine. I don’t want to appear unchivalrous. God, I’m not as flexible as I used to be. Is the ground actually dry? You’re not lying on deer poop or anything?

It’s just cold.

This is my good leather jacket.

You’re vain. But I learned that about you the first time we met. Get down here already.

Okay, okay. Yup, it’s a tree.

A beautiful tree. The most beautiful tree.

I don’t know that it’s more beautiful than, say, the three or four thousand other trees we’ve seen today. Besides, it’s dead.

It isn’t dead.

Clearly that’s a dead tree.

It’s almost winter — all the trees have lost their leaves. That’s why we’re lying on them. I’m quite sure you learned about the seasons at some point in your education.

That is not just a tree denuded of leaves due to the earth’s path in the solar system. That’s a dead tree. Look at the bark. It’s peeling off. You’re looking at a dead, or diseased, or possibly poisoned tree.

Whatever, it’s beautiful.

You know what that’s like? That’s like seeing a corpse and saying, “Gee, that’s the most beautiful person I ever saw.”

I think it might snow today. The sky is the colour of an old pot. Snow brings peace.

It’s as if you’re talking in haiku today. I wish I had a pen.

Walks are good. I’m learning a lot about you. I didn’t know you were quite this cynical. And insecure. Wanting to sound smart.

Oh no, the inevitable psychoanalysis. All right, I accept the diagnosis. Is this a problem for you?

It requires some adjustment.

I’ll try to tone it down.

You know, this really is a good opportunity to learn something more about each other.

We’re not getting up?

Not yet. Tell me something.

What kind of something?

Something about yourself I don’t know. Something you don’t tell people. A secret.

I don’t really like games.

Don’t think of it as a game. Think of it as revealing who you are. I don’t mind going first. Let me think a minute. Oh, I know. When I was twelve years old I stole a yo-yo from the corner store. And then when my best friend Annabelle was accused of doing it, I didn’t fess up.

That’s pretty mean.

Isn’t it? I get hot in the face just thinking about it.

It doesn’t sound like you.

I know! But it just goes to show. You can’t predict. Who knows what I’m capable of? Now it’s your turn.

I really don’t want to do this.

I see you are going to require a lot of patience. All right, I’ll do another one. When I was twenty-one I went through this weird period when I became afraid of everything. It was just a kind of general fear. I wouldn’t go anywhere. I had to quit my job. I had to move back into my parents’ house.

How did it end?

One day I just forced myself to get dressed and walk to the store where I had worked. I was shaking the whole time. I threw up in the bushes along the way. But I went in and asked for my job back and got it. Going out the next day was a little easier. And slowly it went away. Sometimes it feels like it never happened. But I know that deep down I’m afraid it’ll come back.

It must have been awful.

Does it worry you?

I don’t know, I just found out about it. I don’t think so. Not too much, anyway.

Good. You see, that’s the benefit of telling a secret. You feel relief afterwards.

I’m just amazed how easy it is for you to tell me these things.

I don’t find it easy! But at least I won’t have to tell you later.

Well, thank you, I think.

Would you take my hand please?

With pleasure.

Thank you. So now you have to go ahead and tell me a secret. You can’t possibly refuse now.

I’m starting to like this tree.

You’re changing the subject.

I can’t. I’m not like you. I’m sorry. Hey, what are you doing?

Getting up.

Don’t!

What’s the point? Anyway, you didn’t want to lie here. I made you.

All right. Lie down again and I’ll tell a secret.

I’m not going to force you.

I’m doing it of my own free will.

Good.

I don’t really have to think about it. Here’s my secret. I have, in a shoebox at the back of my closet, a letter. A stack of letters, actually.

Who are they from?

Somebody I knew years ago.

Who you were involved with?

Yes.

Written after it was over?

Yes.

I see.

You just let go of my hand. You’re upset.

I did? I didn’t realize. But I’m sorry I started this.

We can stop.

No we can’t. What do the letters say?

I’ve never opened them.

And you’ve kept them all this time? That seems worse somehow.

I think you’re forgetting that I didn’t even know you then.

As if that makes a difference.

So now you’re getting up?

I can’t lie here anymore. I can’t — oh, I don’t know. No, I won’t get up.

I knew this secret-sharing idea of yours was going to end badly. Let’s find a restaurant. Let’s have some nice hot soup.

There’s only one thing to do. You have to open those letters.

Are you serious?

I’m completely serious. I’m going to come over and sit in your armchair and you’re going to sit on the sofa and open those letters and read them. Just to yourself, I don’t need to hear them. I just want to be there.

Is that really a good idea?

I don’t think we’re going to get anywhere if you don’t. At least I can’t.

All right, yes.

I’m going to calm down now. I’m taking a breath. I am. And I’m going to take one last moment to look at the most beautiful tree in the world, living or dead.

Will you at least give me your hand again?

Look! It’s starting to snow.

BLOODY TUESDAY

This here’s my town. It ain’t big, but it’s got good people and they need protectin’. We got a Main Street with a bank and a saloon and a hotel and an ice cream parlour. We got church-goin’ families livin’ here. Also hoors who live above the saloon. Hoors will sit on your lap and play with your tie if you give them money. They’re sad but nice.

Around the town it’s all farmin’ and ranchin’ but mostly ranchin’. On some days a whole herd will come down Main Street with the cowboys movin’ them dogies along. Also there’s Indians livin’ up in the hills. Most people are afraid of ’em but not me. My best friend’s a Moopawk Indian.

Now usually we got a peaceful town. But on a Saturday night it can get a little rambunctious. That’s on account of the cowboys comin’ in from the ranches to drink too much rotgut and ask the hoors to sit on their laps and play with their ties. Sometimes they break a chair for fun or accuse one another of cheatin’ at cards or pour a drink on somebody’s head or pinch a hoor too hard. Bein’ the sheriff, I got to step in. Most of the time it doesn’t take much, just a good hard look that says, Don’t you mess with me. Other times I tap my fingers on my holster. Ar

ound here my reputation for bein’ a quick draw is known to everybody. I ain’t never been beat — that ain’t a brag, just a fact. I tap my gun and the cowboy says, “Pardon me, Sheriff,” and stops whatever he’s doin’. Works like a charm.

A sheriff can’t have a lot of friends, not when you might be arrestin’ people. I got just two. One is Anabelle who is a hoor. Anabelle lets me sit on her lap and plays with my tie and I don’t have to give her no two bits for it. And then there’s Little Feather. That’s my Moopawk Indian friend. Most of the time he’s doin’ Indian things, huntin’ buffalo or sittin’ on his horse in front of a sunset or whoopin’ around a fire. He’s got a sixth sense for knowin’ when I might need his help, and then he shows up, quiet as a shadow. He don’t carry no gun. He uses a tomahawk instead because it don’t make no noise.

So on this particular Tuesday I’m walkin’ along the wooden boardwalk that runs on either side of Main Street, just keepin’ an eye on things. I’m sayin’ howdy to the women in their big hats and pattin’ the little ones on the head because they all idolize me. And then suddenly I hear a whole commotion goin’ on inside the bank. A window breaks, throwin’ glass onto the street, and some guns go off. A second later four men carryin’ heavy sacks with dollar signs on ’em come out. They don’t run off, though. Instead, they go into the saloon.

I decide to check on the bank. As soon as I go through the door I see the bank manager lying on the floor with both his eyes missin’ cause they been shot right out. Also his hands cut off. I walk to the counter and look behind to see Miss Jennifer, the teller, lying on the floor with a big hole in her chest. Miss Jennifer wasn’t a looker but still you don’t like to see that happen to someone.

I go out again. My horse Daisy is tied up. I pat her side and whisper, “Got ourselves a spec o’ trouble, old girl.” Then I head over to the saloon.

When I go through the swingin’ doors I notice how quiet it is inside. The four men who came out of the bank are sittin’ at a table with a bottle of whiskey, playin’ cards. Each of ’em has a big sack by his chair and a hoor in his lap playin’ with his tie. The biggest fellow, huge as an ox, has Anabelle on his lap. Anabelle gives me a quick look, as if to say, Don’t mess with this one, Sheriff.

As if I would back down from my duty.

I walk up to the bar. Behind it the Jew barkeep is shakin’ in his boots. “Pour me one, will ya?” I say and when he does I drink it down in one gulp, doesn’t sting or anythin’. I say, “Why don’t you play that banjo of yers?”

“Vat gut iz muzic now, Sheriff?” he asks.

“Well, I’d appreciate it all the same.” I give him a knowin’ look.

“Okay,” says the barkeep. He takes his ol’ banjo from behind the bar and puts it on his knee and starts to play “Darlin’ Clementine,” my favourite song. I nod and walk to the table where those four bank-robbin’ sons of bitches is sittin’.

“Sorry, fellas,” I say, “but you chose the wrong bank to rob.”

One of the fellas pushes the hoor off his lap and gets up. He’s got a pair of six-shooters low on his hips. The few people inside the saloon move away as far as they can.

“You could do yerself a favour and give yerself up,” I say.

“And you can go play with yer toys,” he says.

I don’t like anyone mentionin’ my toys in a disparagin’ manner. But I know not to lose my cool. “Go ahead,” I say. “You draw first.”

He squints an eye at me and a split second later goes for his guns. He’s fast but not fast enough and quicker ’en you can spit I shoot off his right ear. A little fountain o’ blood spurts up. He gets a shot off but I duck, and even as I hear the mirror shatter I pull the trigger, rippin’ off his nose. Black gunk comes out. “This is for Miss Jennifer,” I say, gettin’ him in the forehead. He wobbles a moment and collapses in a disgustin’ heap.

“Hey, you can’t do that,” says the second robber. He too dumps his hoor and gets up. Only he’s got a bullwhip hidden beside him and uses it to lash the gun right out of my hand. It clatters along the floor.

“Let’s be reasonable,” I say, taking a step toward him. “We can settle this peaceably if you just give yerself up.”

“You is unarmed, Sheriff. I’m going to blow your law-abidin’ brains out.”

He draws his own gun but takes his time like he’s relishin’ the moment. Just gives me time to draw a knife from my boot and slash his fingers to the bone. Which of course means the gun drops to the floor. He’s holding up his hand and looking at it with a dumb expression, and I stick my knife into his gut up to the hilt. I should have aimed higher because smelly poo comes out of him.

“Ew,” says Anabelle, putting her French-perfumed handkerchief to her nose.

“Anabelle,” I say, “come away from that ugly mountain.”

“Who you callin’ ugly?” the third robber says and lunges forward, putting his big hands around my neck. He knocks my hat off, too, but luckily it’s on a string and just hangs behind. Now he’s chokin’ me with all his might, and I start to see stars and the faces of my ma and pa when I spy Little Feather creepin’ under a table. He jumps up and plants his tomahawk into the ugly mountain’s head. It goes in so deep that Little Feather has to push his moccasin against the guy’s ugly back to pull it out again. Then he uses it to cut off the robber’s head, which rolls across the floor with the tongue lolling out.

I pick up my gun and point it at the fourth robber. He puts up his hands. “I surrender,” he says.

“Smart of you,” I say. I turn to Little Feather. “Thank you, my redskin friend.”

“Your life is always worth more than mine,” says Little Feather.

“Let me buy you a drink.”

“I don’t touch firewater. Now I will go and dance in a circle.”

Little Feather runs out of the saloon.

“You saved us,” says Anabelle. “Come sit in my lap so I can play with your tie, no charge.”

“In a minute,” I say. “I still got some rough justice to do.”

That’s when I take the fourth robber outside, put him up on Daisy, and tie his hands behind his back. There’s a half-dead tree in front of the ice cream parlour. I put a noose around his neck, fix the end to a high branch, and yank Daisy out from under him. As I’m not bloodthirsty by nature I do not enjoy the sound of the robber squealing like a drowning pig until his air runs out.

Then I head back into the saloon. It’s a good day’s work for a sheriff and I figure I deserve another drink. Besides, Anabelle is waitin’ for me.

ROSIE

Everybody liked her. She worked in the fashion-dress department, after being promoted from women’s shoes, and was known to have one of the best sales records in the store. It wasn’t just that she knew the products — it was how she could look at a woman and size up not just what was right for her according to size, age, etc., but also how she wanted to be seen. Customers were loyal to Rosie and asked when she’d next be on the floor. They would come in and find that she had put something aside, a dress “that must have been made just for you.”

Everybody liked her, but she was my best friend. At least that’s the way I thought about her. I was stuck in children’s toys, arranging the boxes of games, the plush animals and Barbie dolls, the cowboy outfits and plastic guns. The toy department was just across from dresses so that mothers could leave their children for a moment — which meant leaving them with me. I felt like I’d never get out of that department. Then one day Rosie asked if I wanted to take my lunch break with her, and we went to Lander’s Cafeteria next door where she listened to all my complaints. “Honey,” she said, “it’s okay to find the kids annoying but it’s not okay to show it. You have to flatter the parents and make them feel good about their brats.” She told me a lot more that made sense and as I followed her advice my sales went up. The floor manager, Mr. Constantine, became nicer to me. I could

see myself getting promoted to small appliances or even lingerie.

We started to take all our lunches together and to spend time on our days off, too, going to a matinee, double-dating at a restaurant with dancing (she always cared more about the dancing than about the man whose arm she was on). She would come over to my apartment and we’d turn on the radio and do each other’s nails. I must have told her my entire life story, especially my failed romances and near-engagements. “Don’t you worry,” she always said. “You’re a catch. None of those louts was good enough for you, but like the song says, you’ll know when the right one comes along. Then I’ll dance all night at your wedding.”

“Dance? You’ll be my maid of honour.”

“Now you know that’s not going to happen.”

“Because you’re Negro or Chinese or something? You think I care?”

“Actually, I’m a whole mix of things. I call myself Polynesian. But it will matter to your family and you don’t need that kind of headache, not on your wedding day.”

I looked at her with so much fondness. “Let me find the guy first and then we can argue about it.”

At Christmas time my two flatmates and I decided to have a party. Of course there was a store party but it was so phony, the bosses pretending to be our friends or drinking too much and getting fresh. At our party there were only people we really liked. We had a tree that touched the ceiling, lots of food and booze, a stack of Benny Goodman records. We packed the place. It was noisy and fun and, as the night went on, a little wild.

My brother was one of the guests. He was two years younger than me and hadn’t yet found his feet. He never stuck at one job for long and had to live with our parents outside the city. He’d had a girlfriend I didn’t like very much and wouldn’t you know she broke his poor heart. As far as I knew he hadn’t gone out since, so my ears pricked up when he whispered to me, “Who is that?” He was looking across the room.

“I’ve told you about Rosie.”

“About a million times. But I never saw her before. Come and introduce me.”

My brother looked like someone had blown fairy dust into his eyes. I took him over and of course Rosie was gracious and charming. I left them to check on the food and when I looked back I saw them still talking. The party went late but always when I looked they were together. Already I was fantasizing about Rosie as my sister-in-law. And then, some time after one in the morning, I saw her walk quickly to the door and leave the apartment with her coat.

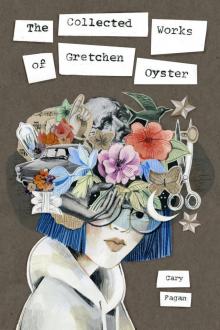

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster

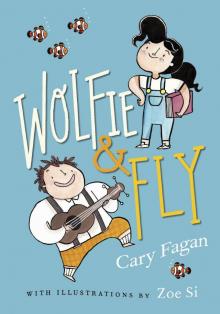

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster Wolfie and Fly

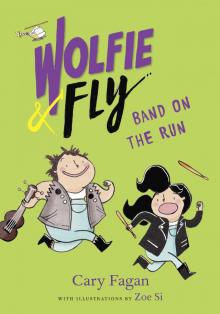

Wolfie and Fly Band on the Run

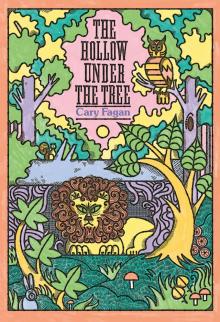

Band on the Run The Hollow under the Tree

The Hollow under the Tree Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas

Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas The Big Swim

The Big Swim The Old World and Other Stories

The Old World and Other Stories Danny, Who Fell in a Hole

Danny, Who Fell in a Hole A Bird's Eye

A Bird's Eye My Life Among the Apes

My Life Among the Apes Banjo of Destiny

Banjo of Destiny Mort Ziff Is Not Dead

Mort Ziff Is Not Dead