- Home

- Cary Fagan

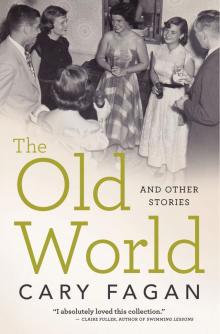

The Old World and Other Stories

The Old World and Other Stories Read online

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

Novels

A Bird’s Eye

Valentine’s Fall

The Mermaid of Paris

The Doctor’s House

Felix Roth

Sleeping Weather

The Animals’ Waltz

Short Fiction

My Life Among the Apes

The Little Black Dress: Tales from France

History Lessons

Nonfiction

City Hall and Mrs. God: A Passionate Journey Through a Changing Toronto

THE OLD WORLD

and Other Stories

CARY FAGAN

Copyright © 2017 Cary Fagan

Published in Canada and in the USA in 2017 by House of Anansi Press Inc.

www.houseofanansi.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

All of the events and characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace ownership of copyright materials. The publisher will gladly rectify any inadvertent errors or omissions in credits in future editions.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Fagan, Cary, author

The old world and other stories / Cary Fagan.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4870-0146-9 (paperback) - ISBN 978-1-4870-0147-6 (epub)

- ISBN 978-1-4870-0148-3 (mobi)

I. Title.

PS8561.A375O43 2017 C813’.54 C2016-906002-0

C2016-907023-9

Library of Congress Control Number 2016958335

Cover design: Alysia Shewchuk

Cover image: Unknown

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

For Rebecca, now and always

CONTENTS

Adults

The Call

Fortune

We Have To Be Careful

Jump

Mrs. Organdy, Naked

Bad Words

Tell Me a Secret

Bloody Tuesday

Rosie

Jealousy

Who I’ve Come For

Greenlees!

I Spare Myself Nothing

Civilization

Bad Rufus

Look Here

Inspiration

Granger

That’s My Boy

Come Back

Day Off

You See All That

The Old World

Minutes of the Meeting

The Traveller

Who’s Sorry Now?

The Six

Subversion

Fate

Charisma

Tiny History

You Should Have Come

Invisible

Where We Are Now

Acknowledgements

About the Author

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Many years ago the photographs in this book became separated from their original owners, faces unrecognized, settings a mystery. They floated through this world, as if on a sorrowful wind.

Of course there are millions of such images, but these thirty-five have found their way to me. I have given them stories to replace the ones they have lost. And while the stories are as varied as the photographs themselves, I imagine them belonging to one history, found in an album that might belong to any of us.

ADULTS

It was the first adult party I ever held, although we weren’t really adults, not quite. But it was the end of high school, when everything would change and we all knew it and so I desperately wanted to mark it in some way — not by getting drunk at the lake, or racing in some boy’s car, or just by the graduation ceremony and the dance that would follow. I wanted a party of my own, where people would act civilized and talk about interesting things and we would see in ourselves the women and men we were about to become.

At least that’s how I see it now, all these decades later, when I’d be surprised if a stranger could look at me and see the girl I was then. I wanted a new pretty hairstyle and shoes with heels. I wanted to greet people at the door and play records just for listening and eat finger sandwiches and say “Do you remember five years ago when we were kids?” and “I think politics is a worthwhile career” and “Don’t you agree that Nat King Cole was a better pianist than a singer?” I wanted to make a list of who should come and who I felt obliged to ask, and revise it over and over, and spend evenings sewing my new dress with my mother nearby to help with the hard parts. I wanted to spend the afternoon of the party in the kitchen with my two best friends, Matilda and Elizabeth, cutting up celery and making dips and laughing as we spread icing on the cake, which would be cut into squares. I wanted to beg my father to let us have punch, something with a little alcohol in it, and he would pretend to be scandalized (as if he didn’t know that everyone drank) but finally give in and then insist on making it himself because nobody could possibly make punch the way he could.

And I wanted every moment, every second of the party to be vivid and alive, and for it to go past midnight when my friends would help me clean up and then Dad would drive them home, and afterwards I would lie in bed, absolutely unable to sleep, smiling about something I said, or somebody else said, or how that drink got spilled and people bent to clean it up and how grown up everyone acted and how full my heart was, not with being scared as it had been for weeks now but with a most wonderful, wonderful feeling.

And it happened. It happened in just the way I imagined except that everything was the littlest bit disappointing. Choosing the guests, picking the dress pattern, making the sandwiches — all of it felt flat, no matter how I tried. Mattie and Liza didn’t seem to feel that way, and I didn’t know what was wrong with me, whether I had just spent too long imagining it or could never live in the moment but was always stuck inside my own head, but whatever the reason it was making me feel worse by the minute.

We dressed for the party and then waited, and of course George Francey arrived first and immediately began to tell stupid jokes. Then two more came and three after that and then a rush. I remember we were standing in the vestibule, because a few people were still coming. My father had poured us all punch, and we stood there chatting, polite and self-conscious. I could hear people in the living room talking about the Soviet Union and Elvis Presley, and it sounded just as phony as could be. I had a sudden urge to run upstairs to my room and shut the door and throw myself on the bed and cry.

And then Justine came in, and the sight of her raised my spirits a little because she’s just that sort of person. Behind her came her cousin, slowly and reluctantly, stooping the way tall boys can sometimes when they’re embarrassed by their height. Justine hadn’t wanted to bring him but had telephoned at the last moment to ask because he was visiting for the weekend and really, she said, h

e was all right, a nice-as-pie farm boy who didn’t know a lick about town living. Justine started telling some story and for a full two minutes forgot to introduce him. And her cousin just stood behind her, looking as if he wanted to disappear into the wallpaper, but finally she remembered, and I held out my hand and said I was glad he could come. He looked up at me (his eyes had been on his shoes), and then he didn’t look away and we made just the most unimportant small talk and I felt something open inside me.

My father brought the new guests punch and then asked Justine’s cousin a few questions about how the crops were looking so far, and then he and my mother took themselves upstairs and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Voices became more relaxed, and people laughed, and we all moved into the living-dining area. Suddenly the conversations sounded real and smart and funny, and I moved around the room, spending time with this person or that, being part of a group or circle and moving on again, and I couldn’t have said what was different, what had lifted the grey film from my eyes. I didn’t talk to Justine’s cousin, but I caught sight of him from time to time, standing in a corner examining a little porcelain figurine, or slowly eating from a bowl of cut-up fruit as if hoping it might last all night, or lingering just outside a group of boys talking about the past football season.

It must have been eleven o’clock when I found him on the front porch. Everyone who wanted to smoke went into the back yard where there was a picnic table, so he was alone. He started when he saw me and apologized and said he was looking at the moon. It was almost a full moon and would be in another day, he said, and so we looked at it together, which I thought was as corny as anything. Crickets chirped in the dark. I asked him about his plans, and he said he was going to attend veterinary school and afterwards wanted to come back to the area and serve the farmers. He was especially interested in looking after horses, although of course it was mostly going to be cows and pigs and sheep. And then he asked about me and I talked about teachers’ college and how I’d always liked being with little kids and how I’d run a Sunday school and had volunteered at the library, and he said that he could see how kids would like me, which I considered pure flattery. We had about a half hour on that porch before Mattie stuck her head out and said we ought to serve cake, and I said just two minutes, and Justine’s cousin took that time to ask if he could come and see me the next afternoon and perhaps we could go for a walk, and I said yes, that would be nice.

And here I am now, here we are, and I’m old and you’re old, only you’re asleep and I’m inside my head once more, thinking about how it’s all gone by. Thinking how I haven’t had enough of those moments, moments full of feeling like I had standing on that porch with you, that there was always too much day-to-day, just getting breakfast on the table and the kids onto the bus, and then heading off to work and back home to make dinner, and falling dead tired into bed. And I know what you’d say if you were awake, you’d say that I worry too much, that I’m too much of a brooder, as I’ve always been, and that we’ve got more life ahead of us, and we’re going to make the most of it, every second. And I want to believe you, my tall, awkward, nice-as-pie farm boy, even if I’m the sort of person who never quite does.

THE CALL

I wait.

I am waiting.

Yes, I am waiting for the telephone to ring, which it will do at precisely 10:30 this morning. So I have been told. “Expect a call at precisely ten thirty. Be sure to answer it promptly. It is of utmost importance.”

I responded in the affirmative, saluted, and turned quickly to march-step back to my desk. In seven years I have never been told to expect a call. Of course the telephone has rung. Of course I have answered it. A higher-up will make a demand, a subordinate a request, placing into my lap some problem to be solved or, perhaps, sent into permanent limbo. This is what I am good at, why I’ve lasted for seven years in the same position, at this desk where it is warm, where nobody tries to shoot me, where lunch breaks occur at the same time every day and from my briefcase I take out the paper bag with the small meal prepared for me by my Anna. More than once I’ve heard them say about me: “Now that fellow, he knows what to do with a problem. He’s reliable and you can depend on him to make sure it won’t raise its head again. Give it to him and he’ll send it to another department, or wrap it up in requests for information, or demand local and regional interpretations that will never be given.” And when I am praised to my face I never take credit but instead say, “But I am only following the protocols already established,” and everyone will nod as if they know just what I am talking about.

And yet here I am, told to receive a call at precisely 10:30. What can this mean? I was informed of it by the colonel just as I came in at nine, and I have been waiting for an hour and eighteen minutes. It is a good thing that I set my watch by the radio while Anna was packing my lunch this morning. The strange thing is, my telephone has not rung once yet, when three or four times is the norm. Has my line been cleared to receive this one important call? Is there a reason for the advance notice, for the exact specification of time? Have I been chosen to receive this call instead of one of the other officers at the other desks in the other tiny rooms?

Don’t worry, I tell myself. You have done nothing wrong. But is that really true? Have I done nothing wrong in seven years? I think back and remember this or that little incident, a smudging of a signature, a misplacing of a medical report, a box of cigars or other small token accepted. Yet wasn’t I keeping within the spirit of my position? Didn’t I give that box of cigars to the colonel? Surely these small irregularities are not worth remarking on. Surely I have amply satisfied those above me. Does not everyone like me? Haven’t I been careful to make no enemies?

Doom. That’s what I feel — absolute and inevitable doom.

If only there was something to take my mind off waiting. On my desk are several papers placed there to make me look busy. Also a little box given to me from Anna that, when opened, makes a noise like a cricket. Also a book lent to me by the colonel, who expects me to like it as much as he did. Slipped inside is the invitation from him and his wife to their anniversary party, an invitation that I worked quietly to obtain by further ingratiating myself. I was so delighted to receive it that I bent the rules that day and used my telephone to call Anna with the news. And of course she was thrilled and immediately began to plan what to contribute to the buffet table, as well as to devise a list of conversation topics that she might engage in with the colonel’s wife, who is notoriously difficult.

Only one paper on my desk disturbs me at all. It is not official correspondence but a letter from my father. I haven’t answered this letter, nor do I have any intention of answering it, just as I have not responded to any of his letters over the last three years. I will never forgive my father, no matter how many letters he sends. I consider him dead. In this one he writes: Will you never forgive me? Will you continue to ignore my existence, to refuse a father’s love for his son? Empty words! That I haven’t thrown it out already shows only a remaining streak of sentimentality. But I will throw it out, have no doubt of that.

I check my watch. It is 10:27. In three minutes I will receive the call. I wonder how best to answer it. Usually I simply say my name. If the call is likely coming from within the department I might say “Desk three!” Occasionally I employ a simple good morning or afternoon. But I’m not sure what’s appropriate here, and there’s nothing worse than indecision.

In two minutes the telephone will ring.

Another lucky thing is that Anna ironed my uniform last night. I myself polished the buttons and waxed the leather straps. I’ve never understood how the officer at desk two can present himself in so slovenly a fashion, as if he feels no respect for our duties and no need to project an air of competency and firmness. I wouldn’t be surprised if the colonel reprimanded him; you can be sure he received no invitation to the anniversary party. I remember as if it were yesterday the first time I put on thi

s uniform. How strange it felt, and when I looked in the mirror I saw a man taller, more handsome, more commanding than myself. And now after seven years I have become that man. What if this call, for reasons I don’t even know, results in my uniform being taken from me? Who will I be then?

The telephone rings. The usual two short rings — did I expect something different? For some reason I look at my watch and see that it is twenty seconds before 10:30. I put my hand on the receiver and . . . hesitate.

It rings again. What on earth am I doing! Why didn’t I pick it up right away?

It rings again. I snatch up the receiver, fumble it, press it to my ear. “Good afternoon. I mean, good morning! This is desk, ah, this is desk three!”

“Are you all right?”

“Who is that? Anna?”

“Of course it’s me. You sound peculiar.”

“Why are you calling? You know this number is off limits except for emergencies.”

“Yes, but you yourself called me on it about the party. I wanted to ask what you thought of my bringing a fish casserole. Everyone always raves about it, that is if they like fish, but I don’t know the tastes of the colonel or his wife —”

“I cannot speak about this now! Do you hear me!”

“There’s no need to shout.”

“I am expecting a call!”

“You’re expecting a call? What sort of call? Should I be worried? Did you do something wrong?”

“This is not a gossip line! I will speak to you at home!”

I hang up the receiver. Sweat has broken out on my brow and I take out my handkerchief to wipe it away. I look at my watch. It is 10:31. It is one minute past the time I was to expect the call.

I wait.

The telephone remains mute. I wait longer. Nothing. The time is now 10:33. Is it possible that the expected call could not get through because I was speaking to Anna? It can’t be!

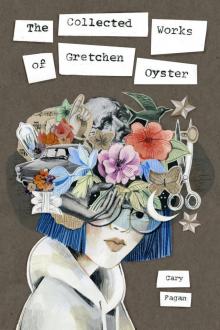

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster

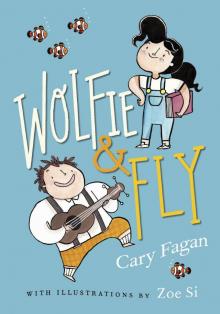

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster Wolfie and Fly

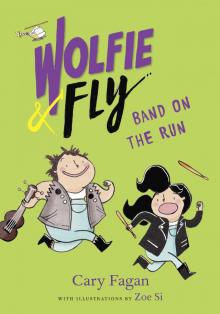

Wolfie and Fly Band on the Run

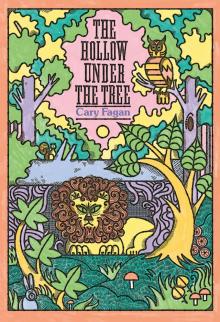

Band on the Run The Hollow under the Tree

The Hollow under the Tree Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas

Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas The Big Swim

The Big Swim The Old World and Other Stories

The Old World and Other Stories Danny, Who Fell in a Hole

Danny, Who Fell in a Hole A Bird's Eye

A Bird's Eye My Life Among the Apes

My Life Among the Apes Banjo of Destiny

Banjo of Destiny Mort Ziff Is Not Dead

Mort Ziff Is Not Dead