- Home

- Cary Fagan

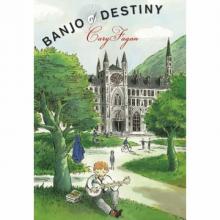

Banjo of Destiny

Banjo of Destiny Read online

BANJO of DESTINY

CARY FAGAN

*

PICTURES BY

Selçuk Demirel

GROUNDWOOD BOOKS • HOUSE OF ANANSI PRESS

TORONTO BERKELEY

Copyright © 2011 Cary Fagan

First published in Canada and the USA in 2011 by Groundwood Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

This edition published in 2011 by

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

www.groundwoodbooks.com

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Fagan, Cary

Banjo of destiny / Cary Fagan ; illustrated by Selçuk Demirel.

eISBN 978-1-55498-141-0

I. Demirel, Selçuk II. Title.

PS8561.A375B36 2011 jC813’.54 C2010-905898-4

Cover art by Selçuk Demirel

Cover design by Michael Solomon

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF).

For Emilio and Yoyo

and Rachel and Sophie

1

The House Built from Floss

JEREMIAH BIRNBAUM lived in a house that looked like a medieval castle. It was surrounded by a moat and ten acres of grounds. Swans and flamingos floated serenely on the water in the moat.

Inside, the house was anything but medieval. There were nine bathrooms, a games room with antique pinball machines, a fully equipped exercise room with an oval track, an indoor pool with a water slide and a hot tub. There was an art gallery with paintings from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, a movie theater, a bowling alley. The floors were heated in the winter and cooled in the summer. Hidden sensors turned on the lights when someone entered a room.

Jeremiah’s bedroom suite was on the third floor. It had a grand entertainment center, private bathroom with a lion’s-foot bathtub and a separate marble shower stall with stereo speakers built in. There was a refrigerator stocked with drinks, and three walk-in closets (one for casual wear, one for formal attire, and one for toys). The desk where he did his homework would have suited the president of a bank.

From his private turret Jeremiah could look down at the artificial waterfall that fed into the moat. His father had stocked the moat with trout. That way Jeremiah could enjoy the experience of fishing without the disappointment of not catching anything.

Jeremiah’s house was built from floss —dental floss. His parents had made their fortune from a dental-floss dispenser that mounted on the bathroom wall. The dispenser used laser light rays and a miniature computer to measure a person’s mouth and dispense the precise length of floss required. The deluxe model let a person choose a flavor, such as mint, raspberry, chocolate pecan, heavenly hash or banana smoothie.

It was something nobody knew they needed — until the television and billboard and internet advertisements told them they did.

And if you don’t have one in your house yet, well, don’t worry. You will soon.

Jeremiah had absolutely everything he could want. He was a very lucky boy, as his parents reminded him every day.

“Not many kids have what you have, Jeremiah,” his father would say. “The most advanced home computer available. A miniature electric Rolls-Royce that you can drive yourself. A tennis court with a robot opponent you can always beat. Do you know how lucky you are?”

“Yes, I do,” Jeremiah said.

He meant it, too. What could a kid like Jeremiah have to complain about?

Absolutely nothing.

•••

THIS WAS Jeremiah.

Curly red hair.

Freckles.

Pale skin that burned easily in the sun. (His mother made him wear sunscreen even in the winter.)

A slouch when he walked, even though his father told him to stand up straight. (“Remember, you’re a Birnbaum.”)

Hands that were always fiddling with restaurant menus, gum wrappers, wax from a dining-room candle.

A total lack of interest in the international dental-floss market.

Jeremiah understood that his parents wanted to give him everything because they themselves had once had nothing. His father, Albert, had worked as a store window cleaner, moving down the street with his long-handled squeegee and his bucket of soapy water. He began work early and he finished late, but he barely made enough to survive. At night, exhausted, he would look up at the cracked ceiling from the narrow bed in his rented room and dream about finding some way to make his life better.

Jeremiah’s mother, Abigail, ran a hotdog cart. She didn’t own the cart. She just worked for the man who did, Mr. Smerge. Mr. Smerge complained if her customers used up the condiments. “Too many pickles, too little profit!” he scolded.

At the end of each week, Albert would treat himself to a hotdog for dinner, loading it with pickles, onions, hot peppers and sauerkraut. He thought Abigail had a nice smile, but he was too shy to start up a conversation. Instead, he sat on a bench near the cart and ate his hotdog by himself.

One day Albert felt something caught between his teeth. He tried to work it out with his tongue and then, hoping nobody was watching, with his finger.

When he looked up, he saw the woman from the hotdog cart standing in front of him. She was holding out a little container of dental floss.

Albert said thank you and tore off a piece of floss.

“I’ve taken more than I need. What a waste, I’m so sorry,” he said.

“That’s all right, I do it all the time,” said Abigail. “There ought to be a dispenser that gives you just the right amount, don’t you think?”

And that’s when Albert’s eyes lit up.

Jeremiah had heard the story many times about how his parents had come up with the idea for their invention. How his parents’ courtship was spent designing the dispenser. Abigail did the research on laser calculation, computer miniaturization, as well as the dispensing mechanics. Albert learned how to set up a manufacturing operation and distribution network.

Jeremiah understood that his parents had grown up with so little that they wanted only the best for him. But he didn’t see why he had to be a “gentleman,” as his father called it. Why he had to know how to shake hands and call people “Sir” and “Ma’am.” Why he had to wait until everyone else was seated before sitting down himself at the dining table.

“You have to know how to behave around rich and powerful people,” his father said. “They expect a certain standard. Especially from children. Your mother and I never learned these things but you will. It’s why we insist you take all those lessons. So you will be an accomplished and impressive young man.”

Jeremiah certainly did have a busy after-school program. Every day at four o’clock one teacher or another rang the doorbell. For ballroom dancing

. Etiquette. Watercolor painting. Golf. And, of course, piano.

Ballroom dancing made Jeremiah feel queasy. He had to wear a suit with tails and a bow tie. He had to dance around the empty ballroom with a woman old enough to be his grandmother.

“Head up! More manly! Feel the music!” she would snap at him.

Painting lessons were a little better, not that he was very good at it. He tried to copy a self-portrait by Rembrandt but it came out cross-eyed. His imitation of a landscape by Van Gogh looked like somebody’s plate after a spaghetti dinner.

Etiquette was merely boring. He had to pretend to eat a meal without putting his elbows on the table and say, “These snails are delicious.” He got double points off for yawning or rocking his chair back and forth. Playing golf, he broke three windows and clipped Wilson the gardener’s ear. Wilson yelped and dropped the garden hose, spraying Jeremiah’s father who was bending over to smell a flower.

Worst of all were the piano lessons. Because Jeremiah actually liked music. He listened to his satellite radio all the time — pop, jazz, rap, heavy metal, classic rock. But Jeremiah’s piano teacher and his parents insisted that he learn only classical music.

There was nothing wrong with classical music, except that it didn’t interest Jeremiah. Maybe if his parents hadn’t forced him to appreciate it, he would have liked it more. But instead of going out to play he would have to sit up straight and listen to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony while his mother exclaimed, “Do you hear it, Jeremiah? It’s genius, genius!”

Naturally they insisted on piano lessons.

“What do well-bred people do in their spare time?” said his father. “They play classical music on the piano. Isn’t that right, Abigail?”

“Absolutely,” said his mother. “It’s the sign of a good family. We can’t wait to see you in the next school talent night. We’re going to be so proud.”

Jeremiah knew he was sunk. If he tried to argue, his father would remind him that he had once washed windows for a living. His mother would tell him again how she had once sold hotdogs.

“My life,” Jeremiah Birnbaum said aloud as he lay on his bed and looked up at the copy of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel on his ceiling, “is a very expensive nightmare.”

2

O Beloved Fernwood!

EVERY MORNING the Birnbaum chauffeur, whose name was Monroe, drove the limousine up to the front of the house. Jeremiah would come down the grand staircase carrying his briefcase and wearing his school uniform — blazer, striped tie, gray pleated trousers and shiny black shoes. His parents would be waiting at the bottom to inspect him. They would make sure his tie was knotted properly, his shirt had no spots of juice on it, and his socks matched.

Monroe was supposed to hop out of the limousine and open the back door, but he knew Jeremiah hated that. So he let Jeremiah open the door himself. Unless, of course, his parents were watching.

“Where to, Jeremiah?” Monroe said one morning in October. He was supposed to call Jeremiah “Master Birnbaum,” but he knew Jeremiah didn’t like that, either.

“Anywhere,” Jeremiah said. “São Paulo, Brazil.”

“Tempting. How about school, instead?” “Can’t you be like a chauffeur in a movie? The cool kind who just does what the kid wants?”

“I’m sympathetic, Jeremiah, I really am. But we don’t have enough gas to get to São Paulo. And I do think you need at least a grade-school education.”

The Fernwood Academy had been founded 103 years earlier by Lincoln Fernwood iii, the richest man in town. It rose up on a hill above the town and looked like a gigantic haunted house with narrow spires and leaded windows and gargoyles.

Every morning at assembly the students sang the school anthem:

O beloved Fernwood

We pledge our hearts to thee!

Do teach us well, so that one day

We’ll run this fair countree…

Parents paid outrageous fees to send their children to Fernwood. But there were also a small number of scholarships for bright students whose families could not afford the tuition. One of those students, Luella Marshall, was Jeremiah’s best friend. His only friend, actually.

Jeremiah and Luella met in gym class while picking sides for a baseball game. Jeremiah was used to being picked somewhere near the end, if not last. But Luella, who was the captain of one team, picked him second. (“Because you looked so sorry for yourself,” she told him later.) He was so surprised, that she had to point to him a second time.

Being chosen gave him an unusual spark of enthusiasm for the game, but even so he struck out three times, dropped a fly ball and missed two grounders.

“Sorry,” he said to her when the game was over. “I guess I let you down.”

“Nah, I like losing fourteen to nothing. But you can make up for it by buying me a root beer after school.”

“I’d really like to but I’ve got a lesson. I could give you the money and you could buy one yourself.”

“Don’t be a jerk. What kind of lesson?”

Jeremiah hesitated. “Ballroom dancing.”

“Boy,” Luella said, “you need me even worse than I thought.”

Luella’s own family lived in a perfectly nice if rather small house, and Luella took the Number 6 bus to school. Jeremiah had never taken a bus anywhere. He envied her independence.

When he took Luella to his house for the first time, she said, “Wow! Is that a real elevator? You’re not just rich. You’re stinking rich!”

The great thing about Luella was that she didn’t care. Yes, when she came over she was happy to cannonball into the pool, or try to hit tennis balls over the net with her eyes closed, or throw balls down the private bowling alley while hopping on one foot. She even liked the swans in the moat. Jeremiah was afraid of getting too close because they hissed at him, but Luella just hissed back, flapping her arms.

But she was just as happy to have Jeremiah come to her house, where they played Monopoly, read comic books, tried to stand on their heads, or walked to the corner store for a Popsicle.

Sometimes Jeremiah wished that he were more like Luella. He wished that he could do things without having to think about them for so long, weighing the pros and cons. That he didn’t care what other people thought of him.

Luella wore one bright yellow and one striped sock to school because she felt like it. She stood up and told the math teacher, Mr. Mickelweiss, that putting questions on a test based on work they hadn’t studied wasn’t fair. She tobogganed backwards down the school hill, singing the Fernwood anthem in Pig Latin.

Jeremiah wished that he too could be brave and imaginative and even just a little bit wild.

•••

AT FERNWOOD Academy, students were expected to be of sound mind and sound body. So once a season Jeremiah had to endure the school-wide cross-country run.

Being just outside the city limits, the academy was surrounded by fields of wheat, barley and corn. It was well into autumn, and the remaining stalks in the harvested fields had turned dry and brittle.

The students began in a crowded pack, but soon the faster runners pulled ahead. The slowest lagged behind, and the rest spread out somewhere in the middle.

Jeremiah and Luella always ran together. The truth, Jeremiah knew, was that Luella was a much faster runner than he was — one of the fastest in the school.

Jeremiah wasn’t only slow. He also tired quickly. Learning the fox trot hadn’t helped much with his stamina. But Luella stayed with him because she was his friend.

The two of them ran together, Jeremiah moaning about a stitch in his side, or his ankle hurting, or feeling like he was going to faint or die. Fortunately, Luella was a very patient friend.

Jeremiah gasped, “I can’t make it. I think I’m going to barf.”

“Oh, come on,” Luella said, bouncing on her toes. “We’re not

even half way.”

“I feel woozy. I might pass out any minute.”

Luella rolled her eyes. “Okay, stop whin-ing. I know a shortcut. Through that field. Then we can rest until the others catch up.”

“You…saved…my…life…” Jeremiah wheezed.

The old farmhouse looked abandoned, the fence knocked down in several places and an upper window broken. Here and there weeds sprouted from the damp ground.

Jeremiah stepped in a muddy puddle, splashing his leg.

“Yuck. This mud smells awful. For all I know it’s pig poo — ”

Something made him hush up.

Music. It seemed to be coming from the front of the farmhouse.

It wasn’t like anything Jeremiah had ever heard before, a captivating rhythm of plucked notes and sudden strums, melody and rhythm.

Jeremiah and Luella looked at one another and slowed to a walk. The music played on. It sounded weirdly old and jumpily alive at the same time. And as they came around the corner of the house, they heard singing.

Shady Grove, my little love, Shady Grove I say,

Shady Grove, my little love, I’m bound to go away.

Luella put her hand on Jeremiah’s arm.

“Let’s get out of here,” she whispered. “We’re trespassing. It might be an angry farmer with a shotgun.”

“Since when were you ever afraid of anything? Besides, that doesn’t sound like a shotgun.”

It wasn’t that Jeremiah felt brave. He just couldn’t stop himself, for the music drew him on. It galloped through him like a heartbeat.

He kept walking toward the front of the house. Luella slowly followed.

As the music grew louder, he saw a man sitting on the porch’s weathered steps.

He was an elderly black man, tall and slim, with a moustache. His steel-gray hair was trimmed short. He wore a white shirt with a pinstriped vest. His trousers were pulled up at the knees, showing his argyle socks and well-polished shoes. His suit jacket had been folded and laid neatly over the porch rail.

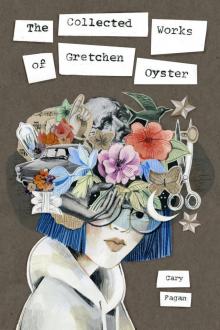

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster

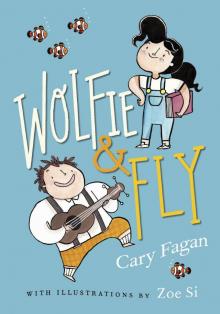

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster Wolfie and Fly

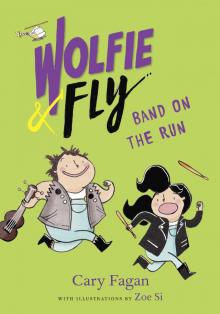

Wolfie and Fly Band on the Run

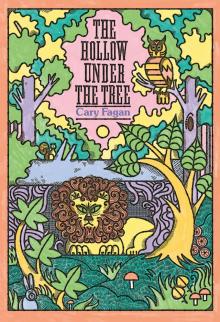

Band on the Run The Hollow under the Tree

The Hollow under the Tree Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas

Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas The Big Swim

The Big Swim The Old World and Other Stories

The Old World and Other Stories Danny, Who Fell in a Hole

Danny, Who Fell in a Hole A Bird's Eye

A Bird's Eye My Life Among the Apes

My Life Among the Apes Banjo of Destiny

Banjo of Destiny Mort Ziff Is Not Dead

Mort Ziff Is Not Dead