- Home

- Cary Fagan

My Life Among the Apes

My Life Among the Apes Read online

Copyright © 2012 Cary Fagan

First ePub edition © Cormorant Books Inc. September, 2012

No part of this publication may be printed, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free 1.800.893.5777.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for its publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) for our publishing activities, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporation, an agency of the Ontario Ministry of Culture, and the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit Program.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Cataloguing information available upon request.

Fagan, Cary

My Life Among the Apes/Cary Fagan.

EPUB ISBN 978-1-77086-106-0 | MOBI ISBN 978-1-77086-107-7

I. Title.

PS8561.A375M88a 2012 C813'.54 C2012-900267-4

Cover design: Angel Guerra/Archetype

based on a text design by Tannice Goddard, Soul Oasis Networking

CORMORANT BOOKS INC.

390 STEELCASE ROAD EAST, MARKHAM, ONTARIO, CANADA L3R 1G2

www.cormorantbooks.com

To Rebecca,

for the best story

“He felt as a conjurer must who is all the time afraid that

at any moment his tricks will be seen through.”

— Tolstoy, War and Peace

The Floating Wife

MY HUSBAND, ALBERT NATHAN ZARETSKY, was, until his retirement, a judge of the Supreme Court of Ontario. Before his bench were heard the most grave criminal and civil accusations in the province, while the most sensational cases were written about in the newspapers and reported on the television news. He was famous (or notorious, depending on one’s position) for allowing Charter arguments to be made and unusual precedents to be cited, and his decisions were appealed before the Supreme Court of Canada more often than most. He looked good on television, for he was a handsome man even in his late years when his hair was still full but absolutely white, and his slightly large features — his prominent eyebrows, his heavy pocked nose, his sensual lips — became more so as his face grew thinner. Actually, he was much more handsome as an older man; when I first saw him, a first-year law student, his head looked too big for his neck and his arms and legs too long.

But Albert had another life, one outside the legal profession. He belonged to a secretive world, what in other circumstances spouses most fear from their partners. In that world, my husband was known as Zardoff the Mysterious, not so much to the public but in magicians’ circles, here in Toronto and also in New York and Los Angeles and, to a lesser extent, London. As a judge he was a forward-thinking champion of individual rights, but as a magician he was a strict traditionalist, eschewing modern technology in favour of the older and, in his opinion, more elegant methods of misdirection and sleight of hand.

I myself am not an expert (far from it), but by all accounts he was a steady performer, skilful without being outstanding. Some praised his stiff, rather formal presentation, while others criticized it. Of course, he could only practise for an hour or so a day after supper, and he performed only as an unpaid amateur (he refused a fee when one was offered) for Boy Scout troops, in hospital wards, and at charity functions. Yet he had, at least as well as I can understand, a fame in the conjuring world equal to his fame in the legal profession. This fame was not for his performances, but for his collection of Victorian and early twentieth-century conjuring apparatus. These objects, acquired at auctions and estate sales, often with the assistance of an agent, he had begun to accumulate in the late fifties, when it was still possible to find important pieces at reasonable prices. He owned a cabinet built for the Davenport brothers, Heller’s secondknown black art table, a pair of pistols used by Anderson in his version of the bullet-catching trick, Chung Ling Soo’s miracle board vanish, and perhaps three hundred more effects, all stored in a museum-quality setting, in a special room built onto the back of the house, which had necessitated the removal of the original tennis court. My husband was famous not only for owning the collection, but for his knowledge of how the illusions were originally presented, and for his generosity in granting access. Magicians came from all over the world, strange men (they were almost always men) who would astonish our children by pulling watermelons out of their ears.

I remember one occasion in the early seventies when, by an accident of scheduling, the premier of the province, who wanted Albert to head a commission on payoffs in the building trades, arrived in a limousine at our house for tea at the same time that Robert Harbin, the creator of the zig-zag girl illusion, arrived by cab from the airport. I answered the door to the both of them and was highly embarrassed, but my husband simply introduced the politician and the conjurer to one another and, after the premier swore an oath of secrecy, the three of them spent several hours in the special wing.

What I thought, standing alone in my kitchen: boys, they’re still and always boys. You must understand that I hated magic. The ridiculous names (Zardoff, for God’s sake), the black capes and top hats and gimmicked canes, the hands that could never be still but always had to be producing cigarettes or “walking” coins over the knuckles. The arguments over the relative greatness of Le Roy and Devant, the inevitable shouting and finger pointing whenever Houdini’s name came up. It was all so childish. As if there could be anything of interest in seeing a man scatter four aces in a deck only to find them in a spectator’s pocket, or a woman in a leotard getting trussed up, shoved into a burlap bag, and locked into a trunk, only to appear a flashing moment later on top of the trunk itself, having changed places with the magician. Why did it matter that the magician had performed a false shuffle, or had used Maskelyne’s method for releasing the chains? It was all child’s play.

WHEN WE MET IN THE early fifties, Albert was not only attending classes but also holding down two jobs, one dipping ice cream bars at the Neilson plant on Spadina Avenue, the other shelving books at the law library. His parents had come from Galitzia and opened a small shoe store in Thunder Bay. Albert was living in a boarding house on Harbord Street run by a Mrs. Mossoff. He was so thin because Mrs. Mossoff put a small amount of the cheapest ground meat into her stews, which she poured over potatoes every night and which Albert often vomited up. In fact, on our first meeting, a blind date arranged by a mutual friend, we were walking down Yonge Street to see the Christmas display in the window of Eaton’s when he collapsed on the sidewalk. I took him home to my mother’s kitchen and fed him.

Back then, his head was full of ideas. He was in love with the law and revered the British legal system, which he saw as an antidote to the grotesque legal distortions enacted by the Nazis. We would go to Diana Sweets for coffee and pie and talk away the evening, Albert leaning forward, eyes aflame, a little spittle gathering at the corner of his mouth as his voice grew louder with excitement and I had to put my hand over his and gently hush him.

He was socially advanced for our time. He encouraged me to believe that, although he foresaw a future for us, he did not want me to restrict my life to that of a housewife. I was an undergraduate with some thought of becoming a nurse but half-expecting that my education and career would end in marriage. With Albert’s emotional and financial support, I became not just a nurse but a doctor, one of the few women M.D.s in the province. I returned to work after each of our three children was born, Albert assuring me that

I could be a good mother even if we needed a nanny to pick up the children from school.

When I first met him, Albert’s interest in magic was a harmless pastime. He had become interested, he told me, upon discovering that an uncle on his mother’s side had been a professional magician in Hamburg, Berlin, Budapest, and Prague. He had found a book at Britnell’s (The Amateur Magician’s Handbook by Henry Hay) and had learned a few simple but effective sleights that he showed to me one evening: making a card rise out of the deck, changing a red handkerchief to green, and so on. This was, I think, the only time I enjoyed watching him perform, mostly because of the pleasure that he himself clearly got out of it. But I was less pleased when, about a month later, we met in the Hart House Library and from his beaten-up briefcase he drew out a wooden box with two little doors. He opened one of the doors and put in a block of wood painted with spots like a die. When he opened the door, the die was gone; apparently it had slid behind the other door. But it wasn’t behind that door either, for it had somehow jumped back into the briefcase. Three or four students in the library seemed to enjoy the little performance, but I was embarrassed and dismayed by it. Afterwards, Albert confided to me that he had just discovered a magic shop on Dundas Street and that he had spent a day’s pay for the trick. I was going to say something, that I wondered if magic was a suitable interest for an adult, or perhaps that it would be better if he saved his money, but I didn’t get the chance, because he suddenly got down on his knee, grasped my hand, and implored me to marry him.

ALBERT WAS NEVER, IN FORTY-THREE years of marriage, an unfaithful husband. He could easily have been, for women found him attractive even without the allure of his powerful position. I suspect that even if he had been tempted, he would have been too mindful of his robes to risk sullying the position he held. If he had been unfaithful, my leaving him would be more understandable, more justifiable to the outside world and to our children, who adored him.

I do not wish to spend a great deal of time recounting the details of his hobby-turned-obsession. The hours spent in the basement practising the linking rings, or donning his custom-made set of tails (tails!) to work at his silent dove act (he had a small aviary and, to the kids’ delight when they were young, a rabbit hutch). Every magician who passed through town was welcome in our house, no matter the time of day. Often they were alcoholic; one used his skills to steal silver. At night in bed, Albert pored over catalogues from magical supply dealers and auction houses.

YOU MUST UNDERSTAND, I KNOW that my husband worked extremely hard at a job of tremendous pressure. He was an otherwise attentive husband and a good father, and he never wavered in his support of my own career as a doctor, a lecturer, and later the co-founder of a women’s hospice. I would have stayed with him, no matter how sick I became of phrases such as “forcing,” “penetration frame,” and “coin clip,” or how often at a dinner party he would unscrew the top of the salt shaker, pour the contents into his hand, and then throw it at the guest across the table only to have the salt vanish. I would have stayed if, after his retirement, he had not decided — no, insisted — on turning professional.

For several months he did not tell me that he had hired a director, a man who had worked with several established acts in Las Vegas and New York, to help him create a stage show. That he had found a 150-seat theatre to rent every Saturday night where he would perform as Zardoff the Mysterious. That he had found a young woman assistant who was lithe enough to fold herself into a basket or fit into that same zig-zag girl cabinet. (Many of my friends would assume that Albert was having an affair with the young woman, a common occurrence in the magic world.) When he did tell me I said no. I was absolutely clear about it, but perhaps he didn’t believe me. Or he believed me but hoped that I would change my mind. Or believed me but decided to go ahead anyway. It was the last possibility that made me realize I could not change my mind even if I wanted to. And so, when he returned from opening night, I was gone.

I slept at the hospital for a few days, then a hotel, and then rented a condominium at Bay and Wellesley. Our kids, young adults by now, were angry at me. Especially our eldest son, who threatened to derail his plans to enter medical school, as if this was a way to get back at me. Our daughter, the middle one, kept her usual neutral stance, while the youngest boy decided to stay with me, although it meant a subway and bus trip to Forest Hill Collegiate every day.

I did not cut off all communication with Albert. We spoke on the phone for a few minutes every day, mostly about the kids but also about our work, never mentioning my having left or his magic show. I only knew it was still running from the entertainment listings. And then some anonymous “friend” sent me a review of the show in the weekly arts paper Now, with what intention I don’t know. The review both mocked and praised Albert’s solemn demeanour, but what caught my attention was the final paragraph.

Zardoff (whose real name is nowhere listed in the program) seems to think that the world has not changed in a hundred years and that people can still be astounded by objects vanishing, endless coins pouring into a top hat, and “spirits” writing messages on chalk boards. He believes that a striking head, lit in profile and with one hand raised, can make an audience grow silent with expectation. And he is weirdly right, or nearly so. But nothing that comes before will prepare you for the show’s pièce-de-résistance, the climactic illusion that he calls “The Floating Wife.” I heard people laugh and, when the lights came up, I saw more than a few surreptitiously wiping tears from their eyes. As for me, I just wanted to know how the damn trick worked.

Naturally I was dismayed and also possibly angry. How could I not be? Surely there were people in the audience on some nights who recognized Albert and knew me as well. It also occurred to me that, given Albert’s nature, I ought to be flattered. And then I discovered that all three of our children had gone to see the show.

“I’m not going to describe it for you,” my eldest son said on the phone. He was still refusing even to see where I lived. “It’s no more nor less than you deserve. I think it would do you good to see it for yourself.”

“I don’t think Dad means anything by it,” my daughter said. “It’s just a good illusion, that’s all. He probably wasn’t even thinking of you.”

“It’s sweet,” said my youngest at breakfast. “It’s so Dad. Go and see it. I bet you’ll cry and you don’t cry easily.”

It didn’t seem as if I had much choice. Still, I waited another week before finally booking a ticket on the telephone, which meant leaving my name on the answering machine. I wondered whether Albert knew that I was coming, and even if he had created “The Floating Wife” expecting that I would see it. The theatre was in a decrepit building, a small, former chicken slaughterhouse. The seats had been rescued from a cinema that was being torn down to put up a multiplex. It was a little more than half full, but there was nobody I knew in the audience. At eight o’clock the curtain did not go up. Nor at eight-thirty. Finally the assistant came out from between the curtains, clearly distraught. My first thought was maybe they were having an affair after all. And then she announced that “Mr. Zardoff” had become ill just before coming to the theatre and had been taken to hospital.

It took me ten minutes to find a cab. I urged him to drive faster, but it did no good. Albert was already dead. He’d suffered a myocardial infarction — a heart attack. They were only just cleaning up the emergency room and he was still on the table. I have seen more than my share of corpses, but when you see the body of the man you have shared your life with you are no longer a doctor.

We had been separated but still husband and wife, and the funeral arrangements fell to me. I wouldn’t have wanted it differently. The service was overflowing with friends, lawyers and judges and other members of the judicial system, the mayor, the premier and several cabinet ministers, people I didn’t recognize. Everyone silently agreed to overlook the fact of our late separation. But what none of them knew was that an hour before the service, I had a terrible

argument with both the rabbi and the director of the Jewish funeral home.

There is a tradition that when a magician dies, his wand is broken in half and ceremoniously thrown into the coffin with him. The rabbi and the director did not want to allow it. In the end, we compromised. I broke the wand (Albert had about two dozen, I just picked one) and placed it in the coffin before the service.

I LIVE IN THE FOREST HILL house again, a widow. Unlike Albert, I have chosen not to retire. My practice is busier than ever, given the current crisis in our health care system, and I have taken on extra teaching duties as well. Exhausted from the day, I go to bed almost as soon as I get home. Every so often the doorbell rings: a magician, visiting town, has come to see Albert’s collection. I let them in, telling them to see themselves out when they are done. Sometimes the magician will ask me about “The Floating Wife,” an illusion that, as far as I can gather, has become something of a legend in conjuring circles. But of course, I can say nothing about it.

Shitbox

I AM TRYING TO BAlANCE the New York Review of Books on my lap while eating Kraft Dinner from a plastic bowl. Well, not actually Kraft Dinner, but a no-name imitation with cheese that is so intensely, unreally orange that it is almost fluorescent. I am struggling through an essay about the Armenian genocide that refers to several new books and also a film by Atom Egoyan. I used to know Atom when Candice and I went to a lot of Toronto parties and openings. I hadn’t quite figured out what I was going to do: make films, write poems, or create some new cross-disciplinary form to capture the paradox of our late capitalist, terrorized, hypererotic Starbucks lives.

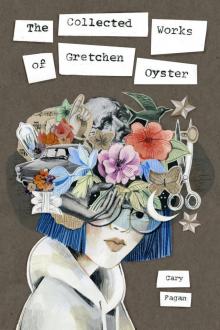

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster

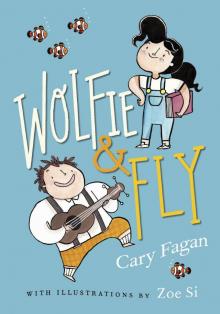

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster Wolfie and Fly

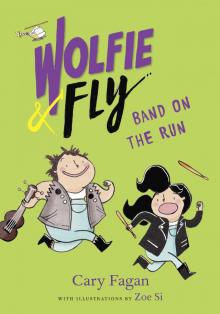

Wolfie and Fly Band on the Run

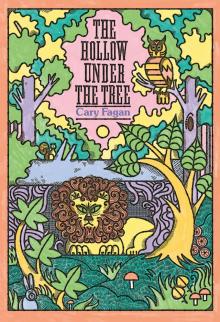

Band on the Run The Hollow under the Tree

The Hollow under the Tree Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas

Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas The Big Swim

The Big Swim The Old World and Other Stories

The Old World and Other Stories Danny, Who Fell in a Hole

Danny, Who Fell in a Hole A Bird's Eye

A Bird's Eye My Life Among the Apes

My Life Among the Apes Banjo of Destiny

Banjo of Destiny Mort Ziff Is Not Dead

Mort Ziff Is Not Dead