- Home

- Cary Fagan

A Bird's Eye Page 2

A Bird's Eye Read online

Page 2

My aunt Hannah had taken the steamship over with Hayim but had almost been forced back to Europe. She had been held for eight days because of her club foot and Hayim, speaking little English and so unable to argue on her behalf, had waited every day until she was released. Even when they were children, he had protected her from bullies and insults.

And how were they to get their own place? Hayim thought, leaning back on his own bed. Here Jacob was fiddling around with ridiculous toys when he had already come up with a perfectly good design for a low-cost pen with a die-stamped nib and the simplest internal reservoir and screw-suction system for taking up ink that Hayim had ever seen. A pen for secretaries, schoolteachers, housewives. Why did Jacob not see the beauty in its simplicity rather than in the complications of his little clockwork monsters? All it would take was a few hundred dollars to produce the first batch. Hayim had three hundred, but he needed Jacob’s money too.

His own he kept in a bank, but Jacob insisted on putting his money in a tobacco tin under the mattress. Hayim looked over to make sure that Malevsky was still asleep and then reached over to pull out the tin. He opened the lid and drew out the pile of bills to count them. Jacob would never have come to Canada to earn this money if Hayim hadn’t pestered him. He had even found Jacob his job. What was the point of money just sitting there, earning nothing? In what way was Jacob’s stubborn refusal fair to Hayim or their sister? Surely Hayim would do them all a service if he started the business going and then brought Jacob into it.

He put the empty tin back and stuffed the money into the bottom of his own drawer. His heart pounded in his chest. But he knew what he had to do. Tomorrow he would become a businessman. And one day his brother would thank him.

My room was the smallest in the house, hardly big enough for more than the bed. A small window overlooked the trash heap in the back garden. Kneeling, I could see my mother coming up from the cellar steps, hands black with coal dust. A smudge on her forehead darker than the birthmark. Kids taunted me because of her mark and reluctantly I had to defend her honour. I usually lost.

It was October 1938, and I was fourteen years old. The windowpane had frost at the edges. I traced my name with a dirty fingernail. From downstairs came the slam of a door. My mother made so much noise, I always knew where she was in the house. My father made almost none, a shadow with no more weight than a single inhalation of breath. Right now he was no doubt at the kitchen table, waiting for his breakfast.

“Benjamin!” My mother calling. “If you don’t come now, I throw your eggs in the garbage.”

I finished buttoning my shirt, glancing idly at the row of toys on the one shelf above the bed. Monkey. Fish. Lion tamer. Bear on a chain. Child riding on a crocodile. I had always owned them. When I was younger, my father had demonstrated them to me (not allowing me to wind them myself), but they hadn’t been touched for years. There was one, a mechanical bird, that he told me was supposed to be his finest creation. Like the others, it was made out of tin and other metals, but with eyes made of glass, dark eyes that looked as if they saw everything and nothing at the same time. It had the shape and colour of a crow but also something of the jay and swallow, an imaginary merging of types. Its wings, folded in repose against its body, were larger in proportion than an actual bird’s, as was its long and pointed beak that somehow looked as if it were smiling. Inside it was a clockwork timing mechanism that set the wings flapping for one minute. Then the wings would halt, stretched out in a gliding position, to start up again a minute later. During the glide, a rush of air was supposed to enter an open slit under the tail and turn a miniature paddlewheel inside, ratcheting up the spring again. My father’s idea was that the bird would stay up until the parts wore out, or it crashed into something, or the weather forced it down. As a child I had imagined it staying up for months and even years, flying over roofs and schoolyards and streetcar tracks and dance halls and dark alleys. And as it flew, my father told me, every so often its mouth would open and it would emit a screeching laugh. But it was the only one of his toys that he didn’t wind up for me, that he had never allowed to come to “life.” He was too afraid that it would drive itself into the ground, or hit a church steeple, or destroy itself in some other way. It was too beautiful to wreck, he said. Actually, as a young boy, I thought it was a little frightening, with those dark, fathomless eyes. Now, however, I hardly noticed it. I didn’t care about any of them, and the skill that my father once had meant nothing to me.

I hurried out of my room, slid down the banister, sprinted past the dim wallpaper curling at the bottom. My father was drinking his coffee and reading yesterday’s newspaper, which he had picked up somewhere. There was a headline about the chancellor of Germany and a photograph of a crowd in a square.

“Can I have the funnies?”

“After I read them,” he grunted.

My mother dropped our plates onto the table. “If they taste like rubber, I don’t care. Take some toast.”

“I want a cup of coffee.”

“You’re fourteen.”

“Give the boy some coffee.”

“Ah, he speaks! Almost never, but when he does, what words of wisdom spill out. You want coffee, Benjamin? Fine. And tonight you can have whisky. Now I have to go. The stall won’t open without me.” She wiped her hands on her apron as she pulled it off. “Benny, you make sure you go to school today. And Jacob, I am afraid to ask what you are going to do.”

“So don’t ask.”

“Tell me.”

“I’m going to read this newspaper.”

“Out of work three months.”

“You haven’t heard? I’m not the only one.”

“There is always work. A day here and there.”

“Not suitable work for a man of my talents.”

“You have no talents. I have been thinking. We can take in another boarder. It will be more work for me, of course. Benjamin, ask Mr. Speisman for more hours after school.”

“I already asked him. He said he has to cut back my hours.”

“More good news.”

“Hitler wants to kill us all,” my father said, rattling the paper.

“With your help,” said my mother, “we’ll starve before he has a chance.”

School was a form of torture, devised by evil beings. I dreamed of being Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon, the Green Hornet. Or someone with special powers, like Superman. If I could have one special power, what would it be? Strength? Flight? Definitely invisibility. Invisibility would allow me to put thumbtacks on Miss Patrick’s chair for her to sit her big ass on. It would let me sneak into Doreen Kessler’s older sister’s bedroom when she was changing and see her titties. I could slip in at suppertime and my parents would stare in amazement as the fork and knife floated in the air and the food disappeared from my plate.

I was restless, small, quick. Physically more like my uncle Hayim, whom I knew even though I’d been forbidden even to speak with him. My father complained that I had shpilkas, ants in the pants. At school I could hardly keep my knees under my desk, my hands from playing with a pencil stub. I would close my fingers around the pencil and imagine that I could make it dematerialize like Mandrake the Magician. But my mind was more like my father’s had once been, always devising, always imagining a better way.

I heard my name and looked up. Miss Patrick was staring impatiently at me.

“Benjamin, march up to the blackboard right now.”

I made my chair screech as I pushed it back. Only Mandrake could save me.

My father did not believe in anything anymore — not in himself, not in family, and certainly not in the deity to which his father had prayed so fervently as he rocked on his heels. But every so often he made me go to the small shul on Brunswick Avenue, whether for my sake or for his I did not know.

“I don’t see why I have to go. It’s just mumbo-

jumbo.”

/>

He cuffed me on the side of my head. I shook it off, then dragged my foot, pretending it was broken. I spent most of my time doing what adults themselves had no faith in. Already I believed only what I could figure out about the world.

“Walk properly,” my father said, giving me a shake. In his hand was the worn velvet bag. A woman leaned out a second-storey window, her breasts pressed to the side of the frame as she reached around to wipe the next glass. The shul was in a small house. Hebrew painted on the glass door. Inside was an old sour smell, a drone of voices. My father gave me a tallis and the two of us draped them around our necks, he muttering a prayer. We stood at the back and I watched the men sway, stoop-shouldered. I couldn’t resist the strange effect of the chanting, how it turned these salesmen and shopkeepers into something that felt holy. What was it? The room, the atmosphere, the sound, the silk and the embroidered letters, the lighting. A powerful effect causing a certain trick of the heart, that’s what caught my attention. And afterwards, I knew, they would once more turn back into salesmen and shopkeepers.

Last year a gang of Protestant toughs pelted us with eggs on our way home. My father didn’t even chase them. In his case, he had been transformed back into a bum. That’s how I saw him, as less than nothing.

My mother wore wool gloves with the fingertips cut off, a man’s heavy overcoat, a washed-out kerchief over her hair. She shooed a pigeon with a deformed foot away from the bin of buckwheat. She sold barley, rice, cornmeal, spices from large jars: cardamom, turmeric, paprika, their intense, dusty colours. She stood under the corrugated overhang while Vogel, the vegetable seller across the way, played Al Jolson on his Silvertone. Before that it was Eddie Cantor, Molly Picon, “Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sascha.” Old records — Vogel hadn’t bought anything new in years. By now the Jewish singers had chased the Italian melodies from her head. She hadn’t spoken to her relatives since marrying my father. It was ten years since she had used her own savings to buy the stall, her husband growing even less reliable with time. For two years, until kindergarten, I had sat on a small wooden crate eating chickpeas and watching the world pass, believing that Nassau and Augusta streets were the crossroads of the world and that my mother was its queen.

Mr. Kober, age seventy-seven, came by. His wife’s legs were no good. Bella poured kasha into a paper bag and he watched carefully as she weighed it. Counted out the pennies. Three months, a husband out of work. In almost a year Jacob had not touched her. As if she wanted him. Sometimes, when he was out late at one of his card games, she would make her own pleasure. Then say to herself, Enough, cow, go to sleep.

She took the pencil from behind her ear and printed on a flat paper bag:

ROOM AND BOARD

$8 Month

Nice Room, Good Meals

These days, maybe eight dollars was too much. She crossed it out and wrote “six,” then tacked the note above the bins.

I was too old to visit her at the stall anymore; I didn’t want to be seen by any kid I knew. I still believed that there was some little hope for me. A lifeline might be thrown, from where I had no idea, but if I watched for it and was quick, I could maybe catch it.

The icebox was stacked with bottles of beer, the kitchen table cleared, and an extra chair brought in from the neighbour’s. Exhausted from standing all day in the cold, my mother refused to serve her husband’s “friends” and had already retreated upstairs. But I was happy to run to the corner for peanuts or a Jersey bar, pick up the bottles, and empty the ashes out of the Blue Ribbon Coffee tin. At the end of the night I would get nickel or dime tips and the biggest winner would give me a quarter. Even then I was making a study of human behaviour, although I didn’t know it. I merely thought that I liked to see the way the players — Bluestein or Levin or Pearlmutter — gave themselves away with little twitches of their eyebrows or sideways looks or movements of their mouths.

The slap of cards, the mumbled raises and calls from mouths dangling cigarettes or, in Pearlmutter’s case, clenching a cigar. When there was nothing to do, I would stand behind my father, leaning on the gas range. He was the smartest player but too cautious about risking his money.

“The boy will learn something from you yet,” said Bluestein, nodding.

“The way his mother talks to me, no wonder I get no respect.”

“You respect your father, don’t you?” asked Pearlmutter. But I didn’t answer, just watched my father rake in the pot.

But after an hour or so, his luck started to run against him. Cards nobody could win with. He tried to slow his losses until the better hands started coming. Once or twice he bluffed, but Pearlmutter was too dumb to fold. And then I saw it.

My father dealt the second card. He did it by drawing the top card slightly back, letting his other hand catch the edge of the card underneath. He saved the top card for himself, which he must have caught a glimpse of. Turned over his hand. Three kings.

Nobody else had noticed. Nobody else had been looking hard enough. I felt myself almost giddy with the excitement of his getting away with it. For the rest of the night I watched my father’s every move. He didn’t cheat often, maybe every three or four hands. He won pots just big enough to keep him a little ahead, a few dollars. There was an elegance to it, the small moves of the hand, shifting away the attention. It was the most impressive thing I’d ever seen my father do.

At eleven o’clock, the men got up, complaining about their luck, the weather, the news from Europe, the continuing lack of business. When the last of them had closed the door, my father came up to me and slapped me hard.

“What are you doing, staring at me like that all night?”

I didn’t answer. I didn’t even mind so much the hot sting of my cheek. Not staring — that was a lesson too.

Most children have a need for friendship that drives them to all sorts of hypocrisy, pretending to like what they don’t, laughing at what isn’t funny, ingratiating themselves with those whose good opinion may influence others. But even then I felt none of that, no need to be embraced as one of the pack. Instead, I kept to myself. Sometimes I went to the library, the big branch with the high arched windows at Gladstone Avenue, where I would sit at a table and read from a book that I pulled off the shelf. I didn’t like made-up stories much; I preferred books on electronics or weather, or else books of history about places I hadn’t even heard of. I didn’t have a library card or know how to get one, and somehow I didn’t think the haughty-looking librarians would give me one anyway, so I never took a book out and so never did finish one.

But what I liked to do best was to walk the city streets, sometimes far from my own neighbourhood. One Sunday afternoon I trudged along the bottom of the Rosedale ravine, and came up between two great houses. I passed between them and onto a circular drive where a chauffeur was giving a long black Packard a shampoo. The chauffeur stared at me and it was as if I suddenly saw my own patched trousers that were too big for me, my scuffed shoes and dirty cap. I would have kept walking, but he stopped his sponging and said, “What are you doing here, Himey? Scram.” So I stopped. And stared at him. And picked up a stone off the drive. And ran full tilt, dragging that stone along the other side of the Packard’s shining paint before taking off down the road with the chauffeur screaming bloody murder.

I walked at night too, slipping out the front door after my parents were asleep or even going out the window, which was dangerous in the winter because of the ice. It sometimes seemed to me as if there were two cities, the one in daylight where people toiled at their jobs and went to the shops and watched their children in the parks, and the one after dark when a whole other species took over. Night people. Washing down the streets. Leaning their heads on tavern bars. Taking swings at each other. It was at night when you could see what the Depression meant, people who were hiding all day coming out and shuffling along, hoping for a handout, a free meal. Others would hop off the trains before they pulled

into the station and look for one of the camps just outside the city. Once, I walked through the grassy oval of Queen’s Park, just behind the red stone building where the politicians made their speeches, and saw a dozen men sleeping on the wooden floor of the concert bandstand with newspapers spread over them. I walked back home and found the two glass bottles of milk left by the dairyman, still cold and beaded. I took the foil top off one and drank it entirely, until there wasn’t a drop left.

And then came the night when I wasn’t careful. I had spent a part of the night walking along the high arch of Davenport Avenue, which marked the edge of an ancient glacier, as a teacher had once told us in about the only bit of information I’d ever learned in school about where I lived. I was on my way home and was cutting through a back alley with tottering wooden garages and scruffy back gardens on either side, when I got jumped.

I didn’t see them until they were already pulling me to the ground, kicking my feet out from under me. Three of them, a year or two older than me, and none I recognized. Fists pounding me in the side, ringing my ear, cracking my mouth. I flailed out hard and caught one of them in the chin with the heel of my shoe, but then a blow to my stomach sucked the wind out of me and I couldn’t even gasp, couldn’t see for the tears and pain.

And then I was alone, lying on the dirty ground. My limbs didn’t want to move. I tasted the salty blood in my mouth. My eyes closed.

I realized that the back of my head was lying in a shallow puddle. But I was still getting my breath back and stayed where I was.

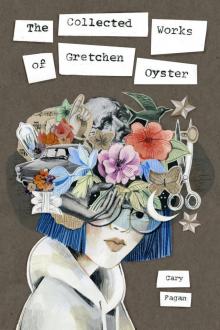

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster

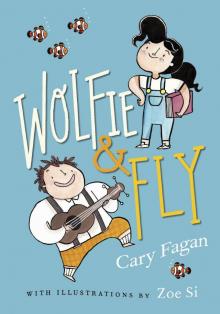

The Collected Works of Gretchen Oyster Wolfie and Fly

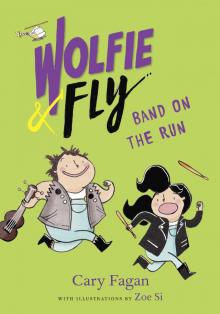

Wolfie and Fly Band on the Run

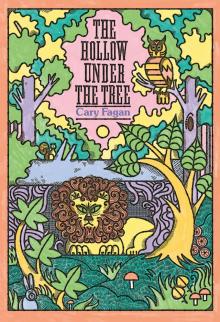

Band on the Run The Hollow under the Tree

The Hollow under the Tree Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas

Jacob Two-Two on the High Seas The Big Swim

The Big Swim The Old World and Other Stories

The Old World and Other Stories Danny, Who Fell in a Hole

Danny, Who Fell in a Hole A Bird's Eye

A Bird's Eye My Life Among the Apes

My Life Among the Apes Banjo of Destiny

Banjo of Destiny Mort Ziff Is Not Dead

Mort Ziff Is Not Dead